In a deeply divided society, one would expect people to vote exclusively for politicians from their own ethnic or linguistic groups. But as it turns out, nothing could be further from the truth. Even a deep ethnolinguistic gap does not prevent Brussels citizens from voting for the ‘other side’. It only gets more intriguing when the parties that benefit most from this kind of voting behaviour are identified.

by Benjamin Blanckaert, Didier Caluwaerts & Silvia Erzeel

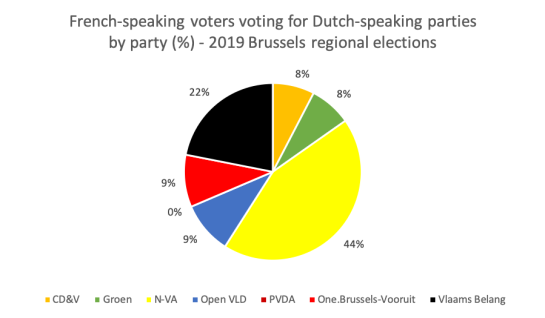

During the last regional Brussels elections on May 25, 2019, the ‘Dutch-speaking vote’ made a historic comeback. Nearly 70 000 (or 15,3%) Brussels residents chose to vote for a Dutch-speaking list over a French-speaking list (Federal Public Service Domestic Affairs). Is the number of Dutch speakers in the Capital Region suddenly increasing or is there more to it? Our research suggests the latter. In Brussels, about 10 to 11% of the French-speaking voters cast a vote for a Dutch-speaking party. Surprisingly, the parties that benefit most from these votes are right-wing Flemish regionalist parties.

Governing amidst division

Democracies that are deeply divided along ethnic or linguistic lines can give their leaders serious headaches. Should they design institutions that avoid, or rather encourage, contact between clashing groups, in order to ensure political stability? Most democracies choose the first option. Elections are organized so that voters can only vote for political parties of their own group, and parties only seek votes within their own community. One country that has almost perfected this logic is the deeply divided Belgium. The Dutch-speaking north (Flanders) and the French-speaking south (Wallonia) each have their own party system, so party competition predominantly takes place between parties situated on the same side of the ethnolinguistic divide. The Brussels Capital Region, however, represents an interesting anomaly in the Belgian political structure. While Flanders and Wallonia are considered linguistically homogeneous areas, the Brussels Region is officially bilingual (and, in reality, multilingual).

Criss-crossing voting behaviour in Brussels

Politics in Brussels is organized around the recognition of two language groups: a Dutch-speaking minority and a French-speaking majority. Unlike the other two regions, it is possible to vote across the divide in Brussels: French-speaking voters can vote for Dutch-speaking parties, and Dutch-speaking voters can vote for French-speaking parties. However, so far little is known about whether voters actually do so. Our analysis of the data from the EOS-RepResent survey, organized on the occasion of the 2019 regional elections, shows that voters do make use of this possibility. Indeed, about 10 to 11% of the francophone Brussels voters cast a vote for a Dutch-speaking party. Since we do not have enough data on the Dutch-speaking voters, we only focused on the French-speaking voters.

The results are astonishing. We found that 66% of the French speakers who vote for a Dutch-speaking party, vote for N-VA or Vlaams Belang, two regionalist parties explicitly focusing on cultural and identity issues. Let’s take a closer look. programs provided?), but it is one of the options available and is easy and cheap to implement.

Supply and demand: asymmetry in the Brussels election market

Which French-speaking voters are attracted to Dutch-speaking parties? Our findings show that these voters are generally more positive toward the outgroup. Moreover, these voters are also more right-wing oriented compared to voters who do not cross the divide. This indicates that right-wing francophone voters find their way to right-wing Flemish parties because of their ideological stance. It is possible that they feel ‘unserved’ by the parties on their side of the linguistic divide and cross-linguistic boundaries because more viable right-wing parties are on offer there.

Apart from ideological considerations, Brussels voters may also vote for ‘the other side’ for strategic reasons, such as to keep a party from the other bloc out of power. However, we should not overestimate the effect of strategic voting. The Brussels electoral system is rather complex and this usually depresses strategic voting.

An alternative explanation might be that an increasing number of French-speaking students in Brussels attends a Dutch-speaking school, allowing them to build a bond with the Dutch-speaking community from an early age. This socialization effect could lower the threshold to vote for a Dutch-speaking party. Finally, the Dutch-speaking parties may also have benefited from a minor modification of the Brussels voting procedure. During the last regional elections, Brussels voters have been shown an overview of all parties (both Dutch-speaking and French-speaking) at the same time on their screen.

Even if the political infrastructure institutionalizes rather than mitigates ethnolinguistic differences, some Brussels voters still take the opportunity to vote for a party from the other language group. And yet, even if some neighbours jump the fence, the Brussels Region is relatively stable, as evidenced by the relatively few protests against the Brussels government. After all, despite its complex institutional setup, the Brussels system is sustainable and well-functioning.

* For further reading, please see chapter 10 of the book: Belgian Exceptionalism Belgian Politics between Realism and Surrealism.

-

Benjamin Blanckaert is a PhD student and teaching assistant in political science at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium. His research interests focus on consociational democracy, Belgian federalism, conflict management and electoral systems.

-

Didier Caluwaerts is a professor of political science at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium. His research interests focus on democratic innovation, deliberative democracy, democratic myopia, federalism and Belgian politics.

-

Silvia Erzeel is professor of political science at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium. Her research focuses on the causes and consequences of gender and social inequality in representative democracy, and also explores new ways of involving disadvantaged citizens in democratic processes.

Add new comment