by Jana Gheuens

In a last-minute intervention, Germany blocked the agreed ban on internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles by 2035. This block risks derailing the decarbonization of one of the EU’s most polluting sectors, and is emblematic of the EU’s challenging history of trying to decarbonize the car sector.

In an attempt to continue the manufacturing of ICE vehicles beyond 2035, the German government demandedadditional guarantees about the use of ‘e-fuels’ – fuels produced using renewable or CO2 free electricity – after 2035. While technically CO2-neutral, e-fuels are very costly and energy-intensive to produce, and are therefore a less efficient way to decarbonize the car sector than electric vehicles.

The inclusion would add yet another loophole for carmakers and would effectively continue the production of ICE vehicles. In doing so, it follows the obstacle-ridden path of prior legislation to reduce the car sector’s emissions.

A rocky start: the 2009 Car Regulation

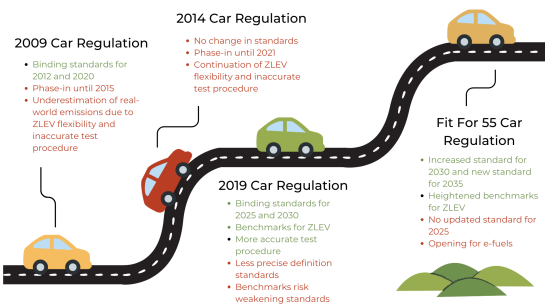

The 2009 Regulation on the CO2 emission performance standards for new passenger cars (hereafter car regulation) established the first CO2 emission standards. After a voluntary agreement with carmakers did not lead to the required emission reductions, the EU set binding emission standards for 2012 and 2020 respectively. However, these standards were insufficient to meaningfully contribute to the EU economy-wide emission reduction objective of 20% by 2020.

Moreover, the 2009 Car Regulation contained many loopholes for carmakers that watered down its contribution even more. For example, the 2012 standard was not fully phased in until 2015, and zero- and low-emission vehicles (ZLEV) were counted more than once when carmakers’ average emissions were calculated to incentivize their uptake. These flexibilities resulted in both a delay and a weakening of the emission standards.

Additionally, the method used to determine the cars’ emissions soon proved to be unrepresentative and further increased the gap between real-world emissions and carmakers’ modeled emissions. As a result, the carmakers only met the emission standards on paper.

Stalling progress: the 2014 Car Regulation

The first revision of the Car Regulation in 2014 failed to overcome these shortcomings.

The revision was limited to the modalities for reaching the 2020 standard and ended up expanding the flexibilities for carmakers. The 2020 standard was not fully phased in until 2021, and no changes were made to the test procedure, even though the growing gap between emission values became increasingly clear.

These flexibilities were mainly introduced after the German government blocked an agreement reached between the Irish Council Presidency and the European Parliament at the last minute. Subsequently, the German block resulted in months of delay and a weaker Car Regulation.

Moving forward: the 2019 Car Regulation

In contrast, the 2019 Car Regulation took some steps forward. It introduced new binding standards for 2025 and 2030, replaced the existing ZLEV flexibility with benchmarks to incentivize ZLEV uptake, and introduced a new, more representative, test procedure.

However, these were accompanied by backsliding on other aspects. To ease the transition to the new test procedure, the 2025 and 2030 standards were defined as emission reductions compared to a baseline year (2021) rather than as nominal standards. As a result, the precise emission standards were unknown at the time of policy formulation, and carmakers had an incentive to have high test emission values in 2021 to minimize their future efforts.

Additionally, the benchmarks for ZLEVs were relatively low and carmakers would have no trouble reaching them, especially considering the fast uptake of electric vehicles in the EU. As carmakers are subject to relaxed standards if they meet the ZLEV benchmarks, the benchmarks will likely lower the car sector’s contribution to the 2030 target.

(Not so) Fit for 55: the latest Car Regulation

This brings us to the EU’s latest revision of the Car Regulation.

As part of the European Green Deal, the EU adopted the climate neutrality by 2050 objective, and it increased the economy-wide 2030 target. As a result, all economic sectors need to step up their climate mitigation efforts – the car sector is no exception to this.

Consequently, the Commission proposed a 100% emission reduction by 2035 compared to the 2021 standard, effectively banning the sale of ICE vehicles after 2035. After difficult negotiations within the institutions, the Parliament and the Council agreed to the 2035 standard, in addition to an increased 2030 standard and heightened ZLEV benchmarks.

Nevertheless, even though the 2035 standard signifies a great leap forward for the car sector, the agreement has shortcomings. Due to the absence of a revision of the 2025 standard, the latest regulation would not significantly contribute to the increased economy-wide 2030 emission objective.

Additionally, the inclusion of a recital that opens the door for the use of e-fuels as a way to reach the 2035 standard risks compromising the transition to less polluting and more efficient electric vehicles. It is precisely this recital that the German government now invoked to block the final stages of the legislative process.

The increased resistance to the ICE ban by some Member States should not come as a surprise, considering the many loopholes carmakers have received in the past – sometimes even after a similar last-minute block. As a result, the car sector has failed to contribute to the economy-wide emission reduction objectives in the past and will continue to do so in the near- and long-term if the political agreement is not respected.

About the author:

Jana Gheuens is a Phd Researcher at the Centre for Environment, Economy and Energy at the Brussels School of Governance and the Vrije Universiteit Brussel. More info

*** This blogpost has been firstly published at GreenDeal-NET on February 10 2023 ***